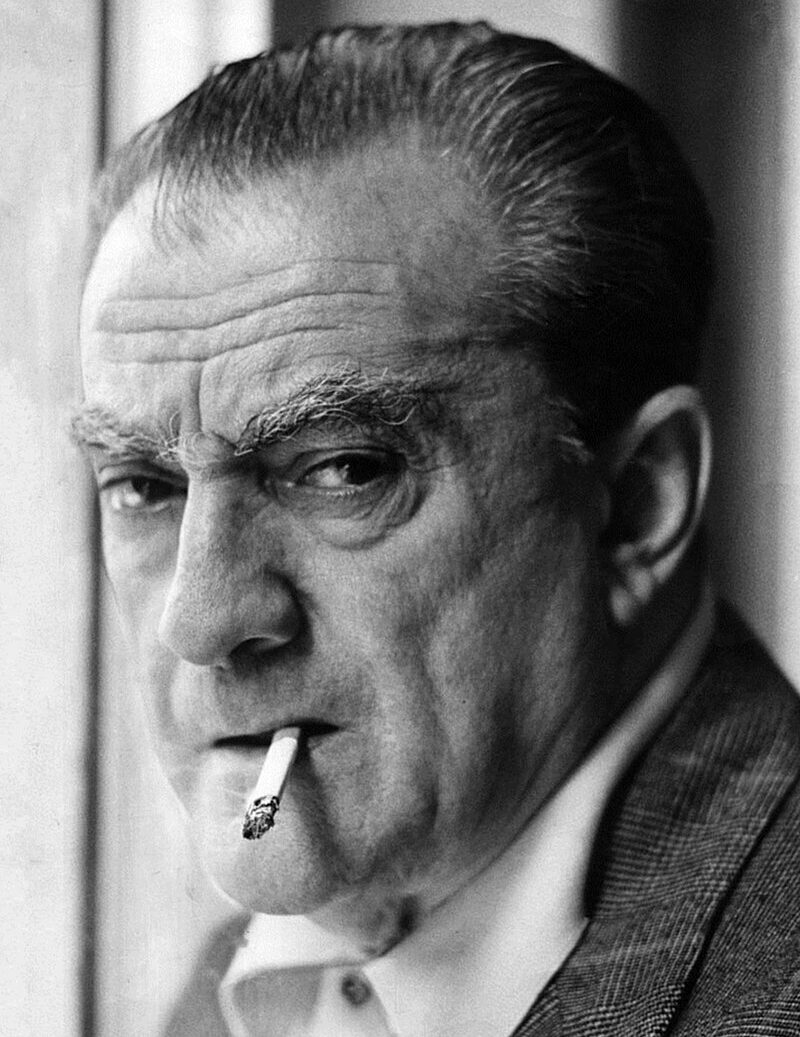

Luchino Visconti di Modrone (1906–1976) was a filmmaker, theatre director, and screenwriter whose works defined an era of Italian cinema. Known for his meticulous artistry, grand historical epics, and explorations of the human condition, Visconti was a pioneer of Italian neorealism and later a master of opulent, visually stunning period dramas. A scion of one of Italy’s most prominent aristocratic families, Visconti’s life and work reflected a unique blend of noble heritage, Marxist ideology, and unrelenting passion for art.

Early Life and Aristocratic Roots

Luchino Visconti was born on November 2, 1906, in Milan, Italy, into the wealthy and aristocratic Visconti family. His full title, Count Luchino Visconti di Modrone, reflected his lineage as a member of one of Italy’s oldest noble families, dating back to the Middle Ages. His father, Giuseppe Visconti, was the Duke of Grazzano, and his mother, Carla Erba, came from a family of prominent industrialists.

Visconti grew up in luxury, surrounded by art, music, and literature. The grandeur of his upbringing—marked by the palaces and lavish estates of his family—would later influence the aesthetic richness of his films. Despite his privileged background, Visconti became a passionate advocate for socialism, eventually joining the Italian Communist Party. This ideological paradox—aristocratic roots juxtaposed with Marxist beliefs—became a central tension in both his life and work.

Introduction to the Arts

Visconti’s early exposure to culture ignited his lifelong passion for the arts. He initially pursued interests in music and theatre, befriending composers, actors, and intellectuals of the time. In the 1930s, he moved to Paris, where he worked with famed French filmmaker Jean Renoir. Under Renoir, Visconti served as an assistant director on films such as Toni (1935) and The Rules of the Game (1939). Renoir’s emphasis on realism and humanism deeply influenced Visconti, shaping his early forays into filmmaking.

Pioneering Italian Neorealism

Visconti made his directorial debut with Ossessione (1943), a groundbreaking adaptation of James M. Cain’s novel The Postman Always Rings Twice. The film is considered one of the earliest examples of Italian neorealism, a movement characterized by its focus on the struggles of ordinary people and the use of non-professional actors and real locations. Ossessione was starkly different from the glossy, escapist fare of Fascist-era Italian cinema, earning both acclaim and controversy for its raw depiction of poverty, adultery, and moral ambiguity.

Following World War II, Visconti solidified his role as a leading figure of neorealism with La Terra Trema (1948). Shot in a Sicilian fishing village with a cast of local non-actors, the film was a powerful critique of social and economic inequality. Though it was not a commercial success, La Terra Trema remains a landmark in the neorealist movement.

A Shift to Historical Epics

In the 1950s, Visconti began to move away from the stark realism of his earlier films, embracing a more elaborate and theatrical style. This shift culminated in Senso (1954), a sumptuous historical drama set during the Austrian occupation of Italy in the 19th century. The film, with its rich costumes, sweeping cinematography, and operatic themes of love and betrayal, marked the beginning of Visconti’s exploration of decadence, power, and historical change.

Rocco e i Suoi Fratelli (Rocco and His Brothers), released in 1960, stands as one of Luchino Visconti’s most acclaimed works. This emotionally charged film offers a poignant exploration of family dynamics, love, ambition, and the social changes in post-war Italy.

Visconti’s 1963 masterpiece The Leopard (Il Gattopardo), based on Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s novel, is perhaps his most celebrated work. Starring Burt Lancaster, Claudia Cardinale, and Alain Delon, the film depicts the decline of the Sicilian aristocracy during Italy’s unification. It won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and remains a towering achievement in world cinema, blending historical insight with unparalleled visual grandeur.

Later Works and Thematic Depth

In his later career, Visconti continued to explore themes of mortality, power, and the decay of aristocratic society. His films often drew on literature, music, and his personal experiences. Death in Venice (1971), based on Thomas Mann’s novella, is a haunting meditation on beauty, obsession, and artistic despair. The film’s lush visuals and Gustav Mahler’s score create an atmosphere of melancholy and existential yearning.

Another significant work, The Damned (1969), examines the moral corruption of a German industrialist family during the rise of Nazism. With its provocative themes and bold visuals, the film earned critical acclaim and established Visconti as a director unafraid to confront the darker aspects of history and human nature.

Theatre and Opera

In addition to his work in film, Visconti was a prolific theatre and opera director. He staged acclaimed productions of plays by Tennessee Williams, Shakespeare, and Chekhov, often collaborating with Italy’s finest actors. His opera productions, including La Traviata and Don Carlo, were renowned for their meticulous detail and opulence, reflecting his cinematic sensibilities.

Personal Life and Legacy

Visconti was openly gay, a rarity for someone of his stature during his time. His sexuality informed much of his work, particularly in its exploration of themes such as desire, repression, and identity. Despite his aristocratic roots, he remained a committed Marxist throughout his life, using his art to critique social hierarchies and advocate for change.

Luchino Visconti passed away on March 17, 1976, at the age of 69. His death marked the end of an era for Italian cinema, but his influence continues to be felt. His films are celebrated not only for their aesthetic beauty but also for their intellectual depth and emotional resonance.

A Lasting Influence

Luchino Visconti’s legacy is one of grandeur and contradiction. As a filmmaker, he combined his aristocratic appreciation for beauty with a deep empathy for the struggles of the working class. His works bridge the gap between neorealism and grand historical spectacle, offering audiences both raw humanity and breathtaking artistry.

From the gritty realism of Ossessione to the opulence of The Leopard, Visconti’s films remain timeless explorations of human nature, history, and the inevitable passage of time. His contributions to cinema, theatre, and opera continue to inspire artists and audiences, securing his place as one of the most influential and revered figures in 20th-century art.