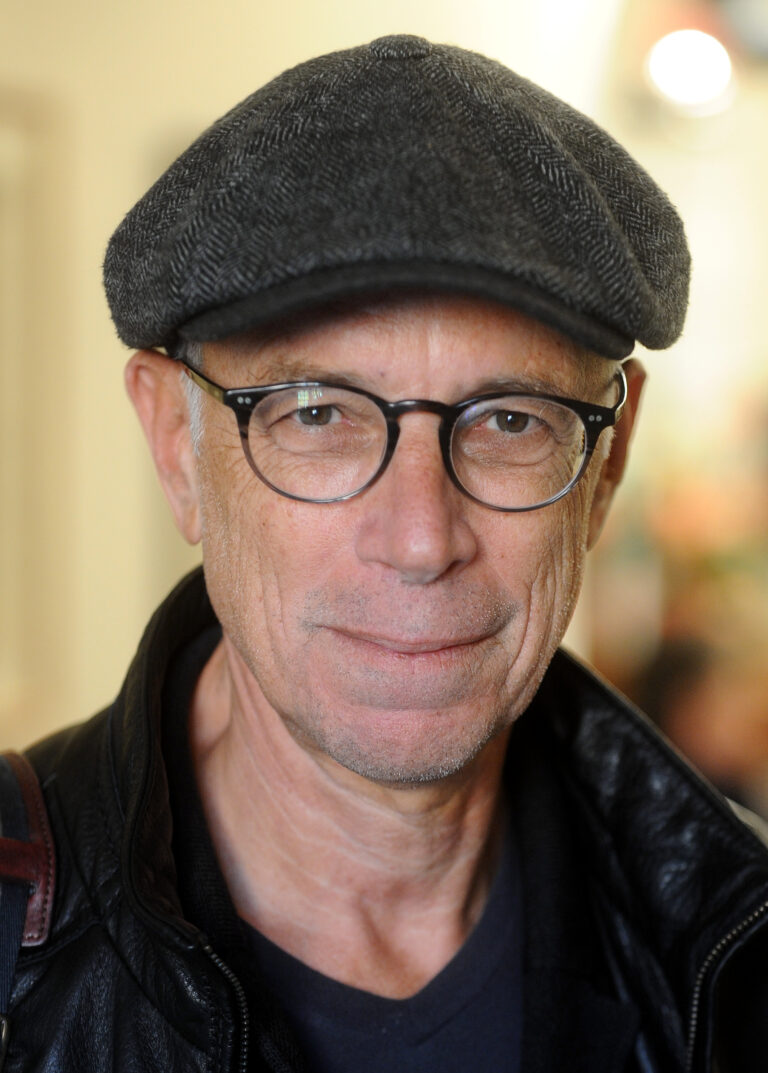

Roberto Rossellini (1906–1977) was a revolutionary filmmaker who transformed the landscape of cinema with his groundbreaking contributions to Italian neorealism. Renowned for his raw and deeply humanistic storytelling, Rossellini captured the struggles, resilience, and moral complexities of ordinary people during one of Italy’s most turbulent periods. His films, such as Rome, Open City (Roma città aperta) and Paisan (Paisà), redefined cinematic language, rejecting artifice in favor of authenticity and emotional truth. Rossellini’s career was as dynamic as his films, marked by artistic triumphs, personal controversies, and an enduring legacy as one of the most influential directors in the history of cinema.

Early Life and Beginnings

Roberto Rossellini was born on May 8, 1906, in Rome, Italy, into a wealthy and cultured family. His father, Angiolo Giuseppe Rossellini, was an architect who helped modernize the city by designing its first cinema, an early connection that would spark Roberto’s lifelong fascination with film.

Rossellini grew up surrounded by the arts, absorbing influences from music, theater, and literature. His education was eclectic and informal, reflecting his wide-ranging curiosity and creative ambitions. In his early twenties, Rossellini began experimenting with filmmaking, working on short documentaries that showcased his technical skill and emerging directorial voice.

The Birth of Neorealism

The turning point in Rossellini’s career—and in cinema itself—came during World War II. Italy was grappling with the devastation of war, fascism, and occupation, and Rossellini sought to reflect these realities on screen. In 1945, he directed Rome, Open City, a film that is widely regarded as the birth of Italian neorealism.

Shot on location in war-ravaged Rome with non-professional actors and limited resources, Rome, Open City is a raw and unflinching portrayal of the Italian resistance against Nazi occupation. The film’s gritty realism, combined with its deeply emotional narrative, captivated audiences and critics alike, earning international acclaim and winning the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival. It remains one of the most important films in cinema history, influencing countless filmmakers and movements.

Rossellini followed Rome, Open City with Paisan (1946) and Germany Year Zero (Germania anno zero, 1948), completing what became known as his “War Trilogy.” Paisan is a six-part episodic film depicting the impact of war on everyday Italians, while Germany Year Zero tells the harrowing story of a boy navigating the moral collapse of post-war Berlin. These films cemented Rossellini’s reputation as a master of neorealism, characterized by their use of real locations, untrained actors, and a focus on ordinary people facing extraordinary circumstances.

Philosophy and Cinematic Vision

Rossellini’s neorealist films were revolutionary not only for their aesthetic but also for their moral and philosophical depth. His work rejected escapism and melodrama, instead embracing a documentary-like authenticity that captured the complexities of human experience. Rossellini believed that cinema had a responsibility to depict the truth, often saying that “reality is always more imaginative than fiction.”

His films explored themes of survival, morality, and resilience, emphasizing the dignity of individuals even in the face of despair. At the same time, Rossellini was a deeply experimental filmmaker, willing to challenge conventions and explore new ways of storytelling. This combination of realism and innovation became a hallmark of his career.

Collaboration with Ingrid Bergman

In 1948, Rossellini received a letter from Hollywood actress Ingrid Bergman, expressing her admiration for his work and her desire to collaborate. Their partnership would prove to be one of the most influential and controversial in cinema history.

Bergman starred in several of Rossellini’s films, beginning with Stromboli (1950), a neorealist drama about a refugee struggling to adapt to life on a remote volcanic island. The collaboration continued with films such as Europe ’51 (1952) and Journey to Italy (Viaggio in Italia, 1954). These films, often focusing on themes of alienation, existential crisis, and emotional introspection, marked a departure from Rossellini’s earlier work.

While their films were not always well-received at the time, they are now regarded as masterpieces, particularly Journey to Italy, which is considered a precursor to modern art cinema and a profound influence on directors like Michelangelo Antonioni and Jean-Luc Godard.

Rossellini and Bergman’s personal relationship was equally groundbreaking but scandalous. Both were married when they began their affair, leading to a highly publicized divorce and eventual marriage. Their union produced three children, including actress and model Isabella Rossellini. However, the intense scrutiny they faced strained their relationship, and they divorced in 1957.

Later Career and Experiments

In the later years of his career, Rossellini moved away from traditional narrative filmmaking and embraced experimentation. He became increasingly interested in historical and educational films, believing that cinema could serve as a tool for enlightenment. Works like The Age of the Medici (1973), Socrates (1971), and Blaise Pascal (1972) reflect his intellectual pursuits, combining documentary techniques with dramatized interpretations of historical events.

While these films did not achieve the commercial success of his earlier works, they demonstrated Rossellini’s enduring commitment to pushing the boundaries of cinema. He also ventured into television, producing educational programs that explored history, philosophy, and science.

Personal Life and Legacy

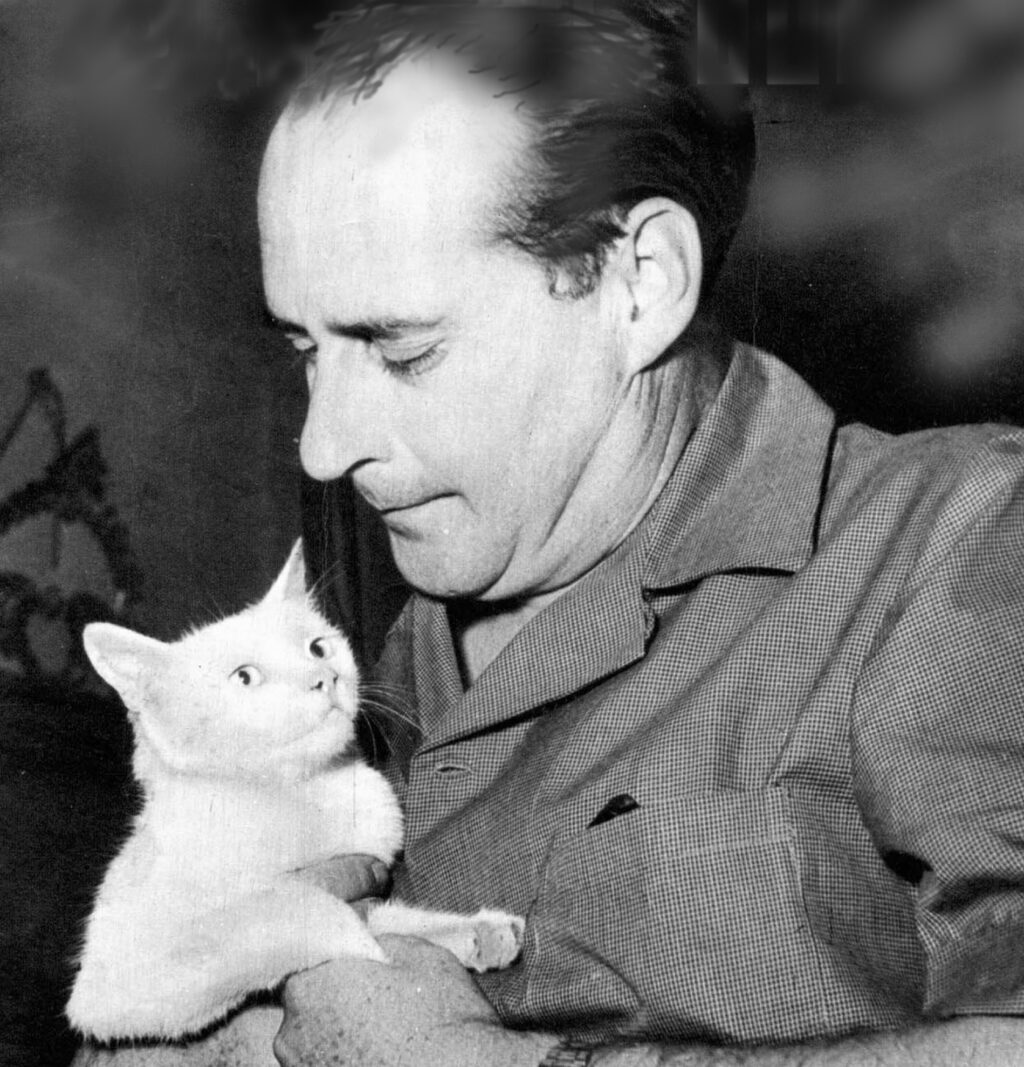

Rossellini’s personal life was as complex as his films. His relationships, particularly with Ingrid Bergman, were the subject of public fascination and controversy. Despite his aristocratic demeanor and reputation as a demanding artist, Rossellini was known for his warmth, curiosity, and intellectual rigor.

Roberto Rossellini passed away on June 3, 1977, in Rome, leaving behind a legacy that transformed cinema. His influence can be seen in the work of directors such as Federico Fellini, François Truffaut, and Martin Scorsese, all of whom drew inspiration from his commitment to authenticity and his pioneering techniques.

Rossellini’s Enduring Influence

Roberto Rossellini’s films remain some of the most vital works in the history of cinema. His dedication to realism, his exploration of moral and social issues, and his willingness to innovate have cemented his status as a towering figure in the medium. From the harrowing streets of Rome, Open City to the existential journeys of Journey to Italy, Rossellini’s work continues to inspire audiences and filmmakers alike.

Beyond his artistic achievements, Rossellini’s belief in cinema as a tool for understanding and compassion remains profoundly relevant. He once said, “The camera is my pen,” a sentiment that reflects his conviction that film is not just entertainment but a means of capturing the essence of human experience.

Roberto Rossellini was more than a filmmaker—he was a visionary who changed the way stories are told and how truth is depicted on screen. His legacy endures as a reminder of cinema’s power to illuminate, challenge, and inspire.