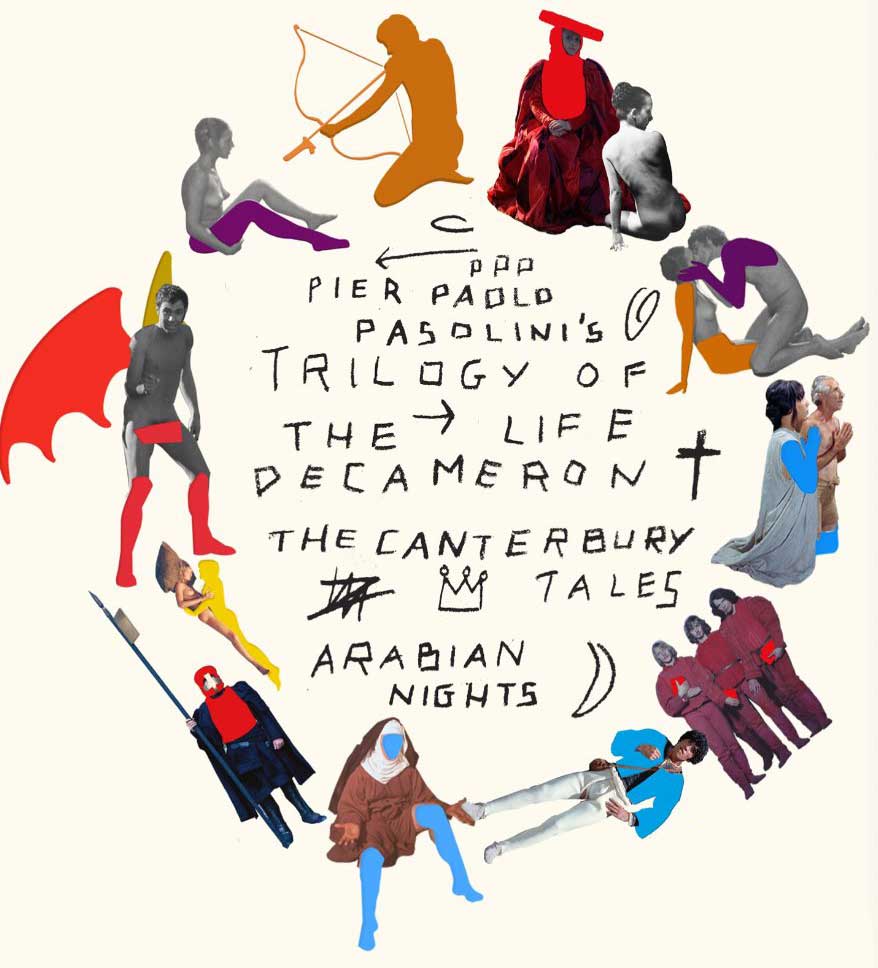

In the early 1970s, the great Italian poet, philosopher, and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini (Salò, or The 120 Days of Sodom) brought to the screen a trio of masterpieces of premodern world literature—Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron, Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, and The Thousand and One Nights (often known as The Arabian Nights)—and in doing so created his most uninhibited and extravagant work, which he titled his Trilogy of Life. In this brazen and bawdy triptych, the director set out to challenge consumer capitalism and celebrate the uncorrupted human body while commenting on contemporary sexual and religious mores and hypocrisies. His scatological humor and rough-hewn sensuality leave all modern standards of decency behind; these are physical, provocative, and wildly entertaining films, all extraordinarily designed by Dante Ferretti (Hugo) and featuring evocative music by Ennio Morricone (Days of Heaven).

The Decameron Pasolini weaves together stories from Giovanni Boccaccio’s fourteenth-century moral tales in this picturesque free-for-all. The Decameron explores the delectations and dark corners of an earlier and, as the filmmaker saw it, less compromised time. Among the chief delights are a young man’s exploits with a gang of grave robbers, some randy nuns who sin with a strapping gardener, and Pasolini’s appearance as a pupil of the painter Giotto, at work on a massive fresco. One of the director’s most popular films, The Decameron, transposed to Naples from Boccaccio’s Florence, is a cutting takedown of the pieties surrounding religion and sex.

The Canterbury Tales Eight of Geoffrey Chaucer’s lusty tales come to life on-screen in Pasolini’s gutsy and delirious The Canterbury Tales, which was shot in England and offers a remarkably earthy re-creation of the medieval era. From the story of a nobleman struck blind after marrying a much younger and ultimately promiscuous bride to a climactic trip to a hell populated by friars and demons (surely one of the most outrageously conceived and realized sequences ever committed to film), this is an unendingly imaginative work of merry blasphemy, framed by Pasolini’s portrayal of Chaucer himself.

Arabian Nights Pasolini traveled to Africa, India, and the Middle East to realize this ambitious cinematic treatment of a handful of the stories from the legendary The Thousand and One Nights. This is not the fairy-tale world of Scheherazade or Aladdin or Ali Baba—instead, the director focuses on the more erotic tales, ones of desire, betrayal, and atonement, framed by the story of a young man’s quest to reconnect with his beloved slave girl. Full of lustrous sets and costumes and stunning location photography, Arabian Nights is a fierce and joyous exploration of human sensuality.